An American October: The Whiskey Rebellion

In October of 1794 George Washington rode at the head of a military force to western Pennsylvania seeking to squash violent opposition to new taxes imposed by the federal government. The tale of this conflict mirrors the history (and perhaps future) of the bold, reckless experiment called the United States of America.

By the late 1780s the states and federal government had accumulated a staggeringly large debt from the Revolutionary War. The Tariff Act of 1789 had done little to generate revenue. Domestic taxation was clearly required for the young nation to fend off foreign foreclosure. In response, Alexander Hamilton spearheaded the creation of a tax on domestically-produced distilled spirits (H.R. 110, The Tariff of 1791).

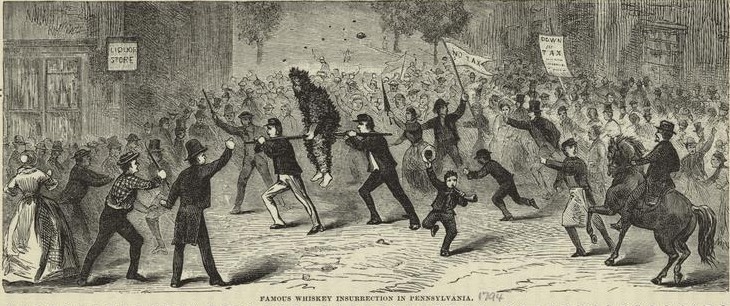

Rural farmers (many also veterans) saw what came to be called the “Whiskey Act” as a regressive and moralistic “sin” tax imposed by far-away urban elites on much-needed supplemental income. The statute’s unreasonable requirements meant the tax was simply ignored by most. Violence (tarring and feathering in particular) toward those trying to collect the tax was common throughout Appalachia.

On the other hand, the problem of war debt was real and the Constitution granted the federal government the power to impose taxes (Article 1, Section 8). A failure to respond to active, vocal and violent resistance to federal law risked at least emboldening other challenges to federal authority (doubtless encouraged by foreign interests) and possibly the disintegration of the Union itself.

Fortunately, Father George was equal to the moment. In August, Washington sent negotiators to talk to the opposition committee. At the same time he authorized raising a militia in the event there was no resolution. The negotiations failed but the militia saw the insurrection melt into the West ahead of their march.

Washington’s comments after the affair are (as always) profound and instructive:

The misled have abandoned their errors. For though I shall always think it a sacred duty to exercise with firmness and energy the constitutional powers with which I am vested, yet it appears to me no less consistent with the public good than it is with my personal feelings to mingle in the operations of Government every degree of moderation and tenderness which the national justice, dignity, and safety may permit.

Join this editor and raise a glass to errors abandoned and moderation consistent with the public good.

Adapted from Wikipedia’s Whiskey Rebellion page